“What am I going to make for dinner, but what do We do about the world?”

Last spring, I didn’t find this question – uttered with raw despair by Girlfriend in Jackie Sibblies Drury’s play Really – particularly striking as I first read the script.

Not overly concerned with the state of the world, I was enjoying the return of sunshine and the confirmation that our visions were being validated: Hillary Clinton appeared on track to become our first female presidential nominee, perhaps president.

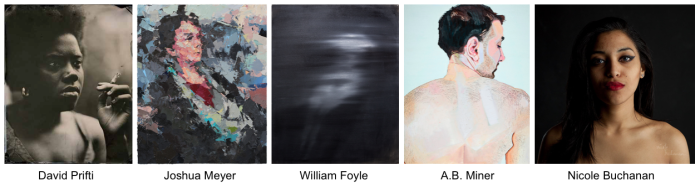

It was in that atmosphere of endless possibility that I joined Matter & Light Fine Art in the South End, and in that same spirit that we embarked on a collaboration with Company One Theatre. Company One would transform Matter & Light into a theater for its production of Really come winter, while Matter & Light would curate an accompanying art show – also titled Really – to enrich the audience’s experience of the intimate, human, and intense play.

In the spring, I could not have imagined how drastically the political landscape would change in a mere eight months. Sitting in the audience on opening night on January 25th, that very same line – that dinner vs. world – was piercing. The script had not altered, yet the words demanded a very different reaction. The paintings and photographs we had carefully selected to reflect the play’s core themes did, too.

Really is, in a nutshell, a play about being human. A white, middle-aged woman (Mother) comes to the loft of a non-white, twenty-something photographer (Girlfriend) so Girlfriend can take her picture. The loft once belonged to Calvin, the only named character. Once a talented, successful photographer, Calvin is now gone, and the two women try to make sense of their loss, their lives, and their post-Calvin identities.

Read Boston’s thoughts about the Really collab: Artsfuse | The New England Theater Geek | The Boston Globe | WBUR The ARTery | Art New England

At one point, Calvin – who appears only through memory – grows increasingly frustrated as Girlfriend talks about “this line that we draw through the western canon / like this white line through Greece and Philosophy and Industry and Technology.” He cuts her off, saying, “…do you know what I think you should do? […] You should listen to me more. […] Whatever it is, this quality – it’s not good for your art. […] It’s like, you are. So. Beautiful. / You are naturally drawn to beauty […}. And when you fight that, it’s. / If you would just let yourself be what I can see you are / I know you could be a really good artist someday.”

In the spring of 2016, I had thought Calvin might be on to something, that Girlfriend’s obsession with the world might be her bottleneck. Calvin was self-absorbed, no doubt, but he was also talented. Magnetic.

Calvin (Alex Portenko) photographs Girlfriend (Rachel Cognata). Image courtesy of Company One Theatre.

Today, that magnetism has a decidedly misogynistic aura. Where I once sought to find Calvin’s love for Girlfriend, I now find him trying to repress her, boil her down to her appearance, put her in her place as nothing more than his beautiful muse. Girlfriend recalls Calvin burning her books because he found them pretentious. In the summer, I smiled at this line as I thought about my own library, my friends’. Now, I see a man who perceives education and curiosity in a woman as ugly, worthy of destruction.

Today, I see Calvin’s talent and charm faltering while his agenda and his need for recognition take center stage. He has become not unlike another “successful” white man with an insatiable appetite for attention, an obsession with winning, and a penchant for judging women by their looks. Today, Calvin emerges as a male archetype with which we’ve become all too familiar.

Art history typically shows us how artists were influenced by their environments; the Really experience has demonstrated how existing art takes on new significance against a new political backdrop. This is the first time in my adult life that I have been witness such seismic political shifts – and watched them not so much transform as deepen what art stands for.

In the springtime, I had romanticized young British painter William Foyle’s nebulous, life-size nudes, which fade into or emerge from darkness. But that was me seeing through an #ImWithHer filter. Given America’s new leader – and the fact that on the day Really opened, he issued an executive order to keep out a very specific group of people – I could no longer escape the real inspiration behind Foyle’s haunting series: archival black and white photographs of Holocaust victims. The #NoBanNoWall filter in action.

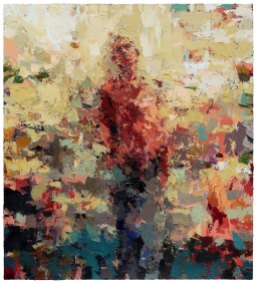

Paintings by Cambridge-based Joshua Meyer that also felt pre-destined for the collaboration from day one have undergone a similar expansion in meaning. When the Really cast had come to the gallery for a read-through in late summer, we had all been struck by the uncanny resemblance between Mother, played by Kippy Goldfarb, and Meyer’s painting Act One.

Actress Kippy Goldfarb, who plays Mother in Really, with Joshua Meyer’s painting Act One.

We noticed similarities between another of Meyer’s abstracted-impressionist works and Girlfriend, played by Rachel Cognata. Another portrait held parallels to Calvin, played by Alex Portenko: a figure seemingly showered in golden light, looking upwards, with an aura vacillating between one of inspiration, pain and resignation.

Meyer’s fascination with how well we truly know the people we love (he almost exclusively paints close family and friends) accentuated the play’s central theme. His palette knife conducts a tug-of-war between getting closer to his subjects and stepping back to see them in context – an approach that pairs beautifully with Really’s exploration of creating intimacy and truly knowing someone.

But Meyer’s work, too, has begun to emit new notes in recent months. Meyer is Jewish, and although one unfamiliar with his work may not see faith or philosophy, they are core building blocks of his oeuvre and path for exploring identity. Next to William Foyle’s images, in our distorted new political light, and with Girlfriend’s thoughts on historical amnesia, Meyer’s work continues the conversation Foyle’s begins – not about Judaism specifically, but about any faith marginalized by those in power. The paintings insist on taking us beyond immediate representation and into history, asking: What happens to a person’s sense of self when parts of their identity are viewed as somehow threatening, criminal, even? And, by extension, what happens when those in power begin playing the types of games of us vs. them the White House is engaging in? I did not think like this nearly as often pre-Trump.

Today’s apparently increasing rather than decreasing fear of “otherness” also comes to the forefront in A.B. Miner’s painting His (II), which explores features we tend to keep hidden, from “imperfections” on our gendered bodies to our sexuality, “exposing vulnerability,” as Miner’s website says, “by revealing what [Miner] (and many people) hide from the outside world – inner turmoil and body irregularities.”

A.B. Miner | His (II), 2014 | 20″ x 16″ | Courtesy of Gallery Kayafas, Boston, MA.

A work that initially lured us with its sensitivity and universal humanity now serves as a reminder of how tenuous certain nearly guaranteed rights really are, of how profoundly invasive public intrusions into something as personal as sexuality can be. Headlines like “Proposed Trump Executive Order Draft Could Curtail LGBTQ Rights” and Caitlyn Jenner’s criticism of Trump’s roll-back on transgender rights come to mind. I imagine this is not what Jackie Sibblies Drury or A.B. Miner pictured when they laid pen to paper and oil to board, but it seems a nearly inevitable thought process when words, images, and politics collide in the Really universe at this moment in time.

The black women in David Prifti’s photographs, too, once merely lost in thought, now appear to be contemplating their fates or bracing for unknown challenge. Beauty has become statement (because, despite what Calvin says, it can and does). Many of them avoid the lens, while the white men look head-on. Is it coincidence or something more?

Coming face-to-face with Prifti’s images this winter, I couldn’t help thinking of a black friend’s post-election post about being accosted by a white man at Jamaica Pond as he “was waving his Make America great again trump hat at me. Telling me ‘this is for you!’”

My ensuing conversations with her pushed my thinking about Really’s role in our current atmosphere. It felt more imperative than ever to find work that would offer insight into Girlfriend’s personal story (Jackie Sibblies Drury specifies that “the performer in this role should be able to relate to being not white or ever passing as white”). In other words, portraiture that would amplify the voices of non-white women.

Thanks to another Really collaborator, Gallery Kayafas, who represents African American photographer and recent RISD graduate Nicole Buchanan, Buchanan’s work joined the Really exhibition, adding perhaps the clearest, most direct link to Girlfriend’s thoughts, fears and potential.

If Buchanan’s The Skin I’m In series photographs appeared alluring in the summer, they have now become quintessential, moving from uplifting and hopeful to insistent, resistant. The images evoke #BlackLivesMatter, #ShePersisted, the global marches that preceded Really’s opening by less than a week.

For Jackie Sibblies Drury, one of the sources of inspiration for creating Really was the work of Roland Barthes, philosopher and author of Camera Lucida – a 1980 book devoted entirely to photography in which Barthes postulated that every photograph brings us into dialog with death, as the subject is either already gone or soon will be.

The experience of living with Really in this time of political and social turbulence, however, demonstrates that the most powerful depictions of human beings carry another power: to bring us into closer dialog with our most immediate reality. Perhaps this is why the current administration is

Photography, like painting and theater, is far from being tied down with what Barthes called “funereal immobility.” Instead, these art forms serve as the most lucid of mirrors reflecting where we are – as individuals attending to practical tasks like meal-planning and as a group considering the state of the world and our roles in its past, present and future.

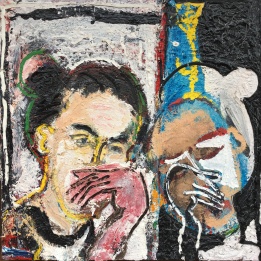

Samuel Messer | The Mirror, 1984 | Oil on canvas | 24.5″ x 24.5″ |

I wish I could continue to watch the show and stroll through the gallery – and through life – with unadulterated hope. But our current reality demands a different response.

At the end of the play, when Girlfriend admits to worrying about polluting the future with her own photography, I no longer question her talent. I hear a reminder to us all, artists and not, that acting on our fears and dreams not only won’t pollute the world, but just may be the only thing that can save it.

________________________